A Brief History of Dudeism

By Rev. Oliver Benjamin

The Dudely Lama of The Church of the Latter-Day Dude

(www.dudeism.com)

From: Fiction, Invention and Hyper-reality: From popular culture to religion

(Routledge Inform Series on Minority Religions and Spiritual Movements)

Edited by Carole M. Cusack and Pavol Kosnáč

Duddha Nature

Often referred to (at least by ourselves) as the greatest cult film of all time, some sort of magical alchemy has been perpetrated in the film’s construction that allows it to transcend the limitations of the conventional format, caveats of cinematic structure, and occasionally, it seems, the very laws of time and space.

The problem with most movies is that they don’t tend to challenge our prejudices or expand our consciousness. There just isn’t enough time for it to get under your skin and alter your existential DNA. Moreover, there’s something osmotic about a written (or spoken) story. By putting the words in the mouths of others, movies take them out of your own head. You become a witness to the events instead of an avatar in the act.

The secret to The Big Lebowski lies in (among other things) a level of complexity and allusive language normally reserved for novels, manifestos and anything by Bob Dylan. Because the film is as meticulously-layered as a mille-feuille, it allows the viewer, with each repeated viewing, to gradually descend into its seemingly-bottomless well of ideas. First time watchers may emerge from their first descent utterly baffled, wondering why none of the plot points were adequately resolved. (What happened to the big bowling showdown? Did the old man actually take the money? Who the fuck are the Knudsens?) But each additional viewing brings a new shift to light at the viewer plumbs deeper and apprehends the interconnectedness with history, philosophy, and ultimately, religion.

It’s often said that you can’t teach someone something by showing it to them or telling them about it, they have to experience it themselves. Most movies merely offer you a two dimensional stream of events. Lebowski, on the other hand is one of the few true 3D movies in history, in the sense that as you watch it, you gradually enter its orb of reality. With each viewing, the movie resonates more and more with your inner hardwired humanity, imploring your inner Dude to reach out to the ideal Dude (Lebowski) and shake his (and our own) atavistic hand. Or, perhaps pass him a joint.

In other words, the more you watch The Big Lebowski, the more you become the Dude. In Buddhism, this would be referred to as finding your Buddha nature. We consider the Buddha to be one of the Great Dudes in History (‘Great Dudes in History’ N.D.). So, basically, you know, same difference.

Hound Dogma

Where religion was once the grand all-explainer with an answer for everything, it now seems a pale shadow of its former self, beset on all sides, declining in influence and popularity, yet still trying to hog the stage. We might say that religion is the fat Elvis of human culture.

Of course, that would be insensitive and cruel to religion (and to Elvis). It’s not religion’s fault that it’s become so misguided and mismanaged. After extended abuse by powerful organizations, it became increasingly gaudied up in sequined costumes with a bloated backup band, pandering to the interests of moneymen and the market, mangling its original greatest hits, the ones that changed the world.

With a hankering towards getting back to basics, Dudeism digs the cozy Axial Age linens out from underneath eons of encrusted ecclesiastical vestments. The Axial Age, we recall, was the period about two millennia ago when most of the current world religions were birthed. Though arising in different parts of the world they all had the same basic maxims: “Just take it easy” and “That’s just, like, your opinion, man.” Early Christianity, Buddhism, Taoism, and several of the Greek philosophical schools (including Epicureanism, Stoicism and Pyrrhonism) all had these as their central messages. Most of these are either gone now, or unrecognizable in their current incarnations. Then again, another of the original Axial Age maxims was “shit happens,” so its prime movers and early acolytes probably anticipated that this doo would come to pass.

Possibly the oldest of the Axial Age religions, Taoism’s primary text, The Tao Te Ching, was a virtual Old Testament of taking it easy. At 81 slim verses, it’s easily the shortest holy book in the world (unless you count Zen, which doesn’t really have a holy book and is sort of against the idea of writing things down). Probably the most important concept in the book, one which pops up in many of the verses, was the concept of wu wei – or action without action, a sense that we should never strive or struggle, but instead try to always take the path of least resistance, else waste our vital energy. Furthermore, in keeping with this enshrinement of emptiness, it also suggested time and time again that the sage is one who knows that he knows nothing (just as Socrates famously admitted, more or less at the same time, and half a world away). And as for dealing with excremental happenstance, The Tao Te Ching prescribed “bending like a flexible reed” when the winds of change fart in your face (Lao Tzu 1963: 79, 138). It sure beat quixotically battling them head-on. Tilting at wind-breaks, as it were.

Surely the image of the Buddha beat both Lao Tzu (the mythical founder of Taoism) and Jesus Christ when it came to suggesting that we “take it easy.” Lao Tzu may be generally be featured riding an ox and Jesus prominently venerated hanging from a cross, but the Buddha is usually shown sitting in meditation, serene as can be, without an evident care in the world. Perhaps more than any other religion, Buddhism codified a series of techniques to aid people to assuage their anxiety, see things from various points of view, and deal with disappointment. It’s all very well and good to tell people not to let the bastards get them down, quite another to show them how to do it. Meditation and the “middle path” were meant to guide people along the difficult so-called “razor’s edge” to enlightenment.

Like their Eastern counterparts, the Western side of the planet seemed to find similar spiritual inspiration in the easygoing. Though the Old Testament noted from time to time (mainly in the more fanciful parts like Psalms and Proverbs) that worry was a pointless endeavor, it’s really in the Gospels where “taking it easy” became exalted to a canonical injunction. Time and time again, Jesus promoted the notion that indolence is next to Godliness: “Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more important than food, and the body more important than clothes?” (Matthew 6: 25) and “Do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own” (Matthew 6: 34). Though Jesus’ ultimate message was that it is their God that will provide for them, it didn’t have to be interpreted as a strict quid pro quo, rather something akin to the provident nature of Nature itself, as enshrined in Taoism’s “ever refilling vessel” (Lao Tze 1963: 60). He differentiates between the pagan supplication for favor and an over-arching sense that the cosmos will appear generous to those who aren’t greedy. “For the pagans run after all these things and your heavenly father knows that you need them” (Matthew 6: 32). Christianity may not have been as easygoing about varieties of opinion as its eastern Axial counterparts, but nevertheless its notion that human knowledge is fallible and that the “vanities” of man should not be held too dearly differentiated the creed from the rigid catalog of superstitions of pagan cultures it supplanted. That is, of course, until the Church rushed in to fill the power vacuum and introduced its own catalog of regulatory superstitions.

What is the sound of shit happening?

Though a lot of the Axial Age insights became buried under the battlements of civilization and power, there’s nothing to say that shit can’t be made to unhappen as well. Perhaps all we need to do to return religion to its original nature is to properly pot it and cultivate it. In keeping with the Axial Age traditions, this would unfold via its fundamental maxims: promoting “taking it easy” and the notion that all concepts are just models (i.e. opinions) of the world, not a hard and unchanging reality.

One of the first steps to bring us back to a new Axial Age (in Dudeism, we refer to it as a “Relaxial Age”) is that the word “religion” needs to be made sense of. Currently religion derives a lot of its power from the fact that, like a moving target, it cannot be accurately pinned down. Terms like God, love, patriotism, and value-added tax are powerful and manipulative because no one really knows what they mean.

Which brings us to the second-most common criticism of Dudeism: that it can’t be called a religion since it recognizes no God or gods. Which is not to say we’re an atheistic religion, but rather a non-theistic religion. We don’t have any opinions on the existence or non-existence of God because we don’t think God has been adequately defined to even pose the question. Asking whether you believe in God is akin to asking whether you believe in Blah. What is Blah? God means many things to many people all over the world. God is love. God is nature. God is the guy you acknowledge during orgasms. If God were a corporation, he’d have to fire his branding department.

Do we believe that there’s some far-out stuff out there that we don’t understand? Of course we do. Even the most dyed-in-the-unwoolly Logical Positivist would admit this. But do we claim to know what it is? Of course we don’t. To do so would be a logical contradiction. And yet this is the foundational modus operandi of most religious catechisms: God is a mystery that cannot be understood by mere mortals; now, let us tell you all about him.

Instead of wasting our time on such a quixotic (and exhausting!) endeavor, we choose to focus on the other, more practical aspects of religious tradition – most importantly, its psychological utility. From the Dudeist perspective, that’s what religion was really all about in the first place. The metaphysics was only in there because physics didn’t exist yet. When it comes to psychological utility, no viable substitutes have emerged to religion, although psychology itself had a good run there for a while.

What’s a Heuro?

For lack of a better (or more familiar) term, we see religion as a heuristic for holiness. A heuristic is a technique used in the sciences to simplify a complex field of data so that it can be more easily understood, manipulated, and made use of. And not just in academia – Human beings use heuristics every day. Without them they couldn’t even get out of bed in the morning. What we call “common sense” is just the panoply of heuristics we’ve accumulated over our lives. Rules of thumb, mnemonics, and educated guesses are all everyday forms of heurism.

Life can be hard and complex, and we need help making sense of it. We utilize heuristics to help cut through and categorize all the chaos and endless decision-making. As Jesus in the Gospels points out, human beings are the only animals that worry and toil – and for apparently no good reason. He suggested that we consider the lilies of the field (Evidently there were no sloths in Galilee) and just take ’er easy instead of getting all worked up over things. His prescriptions in the Gospels went some way towards showing how this might be approached.

All religions do just this: they provide a worldview and package of heuristics which teach us how to behave, how to spend our time, how to treat each other, how to survive, and how to maximize our psychological well-being. The reason animals (and flowers) don’t need religion is because that’s all taken care of by their instincts. Their heuristics are hard-wired.

So what would a “heuristic for holiness” consist of? What is holiness, after all? Unsurprisingly, “holy” comes from the same root as “whole.” Tellingly, it’s also related to the root for “health.” Of course, etymology can be used to argue anything you like, but here it seems likely that the notion of the holy implies something like integrity on steroids. Or, at least, we can choose to interpret it that way. Thus, rather than suggesting something otherworldly and separate from the world (as many religions seem to), the prime objective of “holy” religious practice and tradition might be to render the acolyte whole and hale, both within the realm of his own consciousness and the society and environment of which he or she is part. Put simply (and Dudely), religion helps us get our heads together, man.

The Relaxial Age

Historian Karl Jaspers came up with the term “Axial Age” because he saw it as a profound turning point in human cultural development, witnessing the birth of the great religions, philosophies and worldviews that continue to inform our culture today. Though differing in the details, all of these “isms” aimed to assuage the discomfort everyday humans felt in just being alive (Jaspers 1977).

But why is it that “all life is suffering,” as the Buddha (and virtually every other religious figure) suggested? Religion has tried to address this mystery in various ways. Judaism says we were perfectly well-adapted to nature but then we got ambitious and gave up our birthright. Christianity says we just have to learn to love unconditionally and we’ll once again dwell in an updated version of the Garden. Buddhism says that we just need to evolve until we realize our place in the world. Taoism says you’re not going to fix anything so we should just relax and to go with the flow. Are they wrong? No, they’re all generally correct. The devils, so to speak, are in the details.

One of our great intellectual revolutions took place in the early 1990s though few have noticed yet. At the University of California at Santa Barbara (incidentally, the town where Jeff Bridges, the actor who plays the Dude in The Big Lebowski lives), a field called Evolutionary Psychology was birthed. Prior to its genesis, psychology had become a somewhat bankrupt science, with myriad conflicting schools of thought, all of which disagreed with each other, few of its experiments showing repeatability, and featuring a diagnostic and statistical manual so enormous and bloated that a good number of its students couldn’t actually even lift it.

The simple and elegant principle underlying evolutionary psychology was that our minds were biologically shaped by a long, stable period living on the African savannah. Life was likely fairly copasetic back then, and even when it wasn’t, we were well-adapted to deal with any bummers that came our way. We hung out in groups of about 150 close-knit friends, lived off the land, and basically took it easy most of the time. Most of the problems we have to deal with today came as a result of the rise of agriculture, which forced us to stay in one place and guard our hoard of food. The consequent rise of cities and fortifications led to warfare and disease and massive expansion of social pressures, frictions, expectations and competition. Our brains were simply not (and are still not) designed for this new environment.

Thus, what Judaism, Hinduism, Jainism, Confucianism, Christianity, Buddhism, Taoism, Epicureanism and other Axial Age creeds offered were explanations and prescriptions for dealing with this new “exile” from the world to which we were biologically adapted. Their original messages (parts anyway) are still relevant today, since the basics of life haven’t changed that much since civilization found its first footing: We still have to struggle with the pressures of materialism and social status, the stress of being surrounded by strangers all the time, the burden of learning vast amounts of information, the frustrations of bureaucracy, the prevalence of fear-mongering, and the depressing sense that we are tiny and insignificant drop in a bucket of billions of drops instead of an important part of a caring and loyal tribe.

The UnDude Ages

These new ideas and their recommendations may have helped us for a while. But then, just as we lost our bucolic African “paradise,” the religions meant to help us deal with that loss became quickly usurped by the politics and pressures of empire-building. In many cases the creeds were dramatically modified to exacerbate our discomfort rather than assuage it: Judaism grew to emphasize “otherness” from the rest of the world and the heavy portent of a savior who still has not shown up; Christianity introduced the glorification of suffering, keeping its followers in line with the terrifying threat of hell and an uncertain consolation of an unlikely heaven; Buddhism became mired in superstition and obsessed with the very notions of hierarchy it was mean to jettison in the first place; Taoism abandoned its practical and poetic prescriptions for living in the here-and-now in favor of superstitions surrounding immortality and quack medicine; and Epicureanism became systematically and vindictively crushed by followers of Christianity, only to be reintroduced in the twentieth century as a marketing strategy which purveyed overpriced products.

It hasn’t all been a washout, of course. Under all the ecclesiastical and financial trappings of the organizations we can still see hints of the original charitable, meek and loving Jesus; within the Talmud and Kabbalah we can find exegeses on personal development and virtue instead of adherence to archaic law; within zazen we can find the direct apprehension of Dharma promised by the Buddha instead of the obfuscating distractions of superstition; within Yogism we can find an all-encompassing humility and liberation which counters Hinduism’s ethnic and ritualistic obsessions. And so on.

The problem is that most societies don’t really allow us to order religion a la carte. If only there were a way to distill out the essence from the excess and enshrine it in a new worldview! Certainly some have tried. Aldous Huxley promoted the idea of the “perennial philosophy,” which he said existed at the base of all the great religions. Unitarian Universalism and Secular Humanist movements have tried to refashion religion without religiosity. And many New Age movements have attempted to separate the sweet bits from the hard crusts of all variety of religion. Even celebrated author Alain de Botton penned a book called Religion for Atheists which had several good ideas and a few bad ones, one of which was an annual orgy sanctioned by the state. But nothing has really caught on to any substantial degree (de Botton 2013).

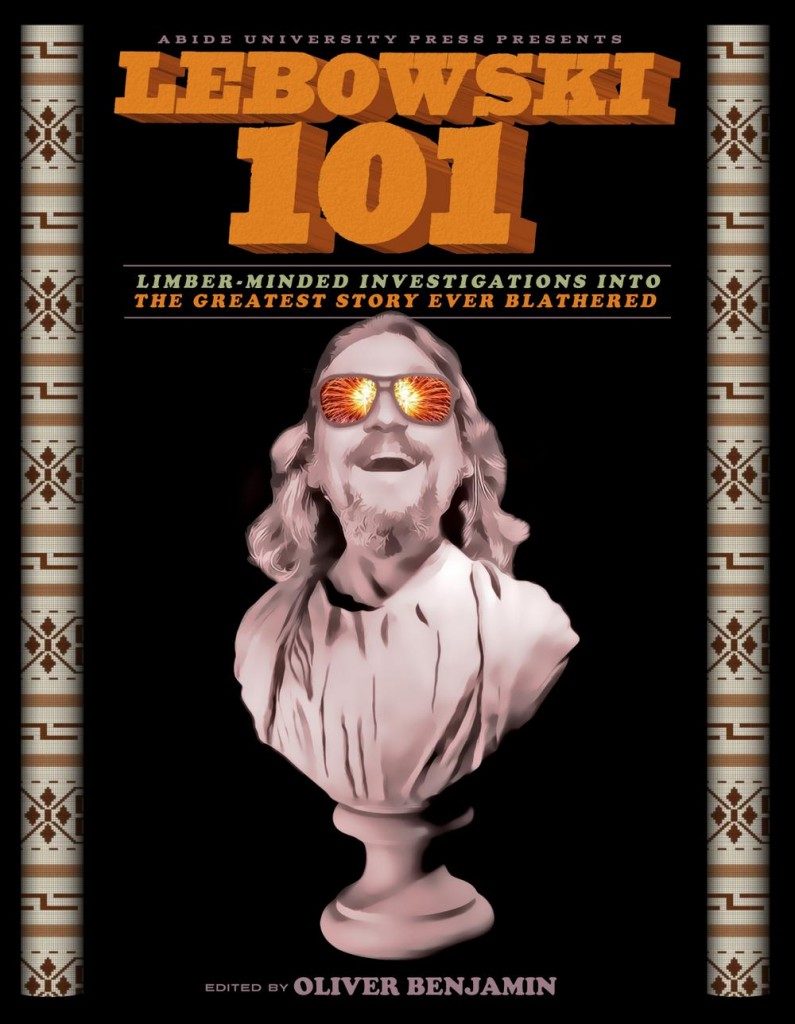

The Dude Vinci Code

No one knows for sure what the Coen Brothers had in mind when putting together an epic like The Big Lebowski. Is it a mere coincidence that its protagonist dresses in a robe and sandals, like the prophets of the Axial age? Are the pepperings of religious metaphor there only for decoration, or are a pedophile Jesus, Nietzschean Nihilists, a militant orthodox Jew, lashings of Eastern mysticism, and an omniscient white-haired narrator all part of a hermetic subtext? It doesn’t really matter. Just as we choose to read “holy” as “whole and hale” we also choose to see enshrined in The Big Lebowski a suitable and very welcome heuristic for holiness. So many of the elements and allusions in the film speak to our desperate human need to “abide” in the world instead of merely surviving it, that it would be churlish to disregard them in favor of maintaining a dismissive literalism.

Though history records the works of so-called great men and generally paves over the bones of the losers, clandestine fragments of fossils have been passed down throughout history. What we call Hermetic traditions or secret societies have generally taken it upon themselves to safeguard holy but endangered truths so that they can’t be destroyed by the fascist regimes who relentlessly end up in charge. Yet only those with the appropriate key can unlock the code. This in mind, we’re prone to wonder: might there be a “Dude Vinci” code that has existed throughout history?

The canon of the Church of the Latter-Day Dude contends that, indeed, Dudeism has always existed, getting its start in the early incarnations of Axial age religions and then, once persecuted, going underground, or at least being relegated to sidekick status. We choose to retroactively baptizing all the disparate strains as “Dudeism,” not to claim them for our own, however, but rather to offer kinship and allegiance and to try and gather together the fragments so that our followers don’t have to reinvent the wheel of Dudeist Dharma. Ours can be seen as the hermetic key to the door of the Dude, one which has always been outward-opening, and more or less unlocked anyway.

The Dude Testament

So what are the tenets of Dudeism anyway? At the risk of being anticlimactic, the subject is too big to be delved into in any depth here. For that further study of our books The Abide Guide and The Tao of the Dude are in order, along with material found on our website, dudeism.com. But suffice to say that virtually everything has already that can be said about Dudeism now, had been said at the beginning, in the form of the first and still most-powerful and unadulterated Dudeist antecedent, that of Taoism. One might say that Dudeism is just an updated version of early Taoism, before its wu wei got infested with woo.[1] Sources we commonly allude to include David Hall and Roger Ames’ commentary on their translation, Dao De Jing and Holmes Welch’s Taoism: The Parting of the Way. One will also find a great deal of Dudeism in Raymond M. Smullyan’s The Tao is Silent. We’re also working on our own new and annotated version of the Tao.[2]

But not just Taoism. As we’ve suggested, the same variety of thought and perspective can be found in the Gnostic tradition of Christianity, in several of the classical Hellenic philosophies, in the yogic traditions of Hinduism, in the Zen traditions of Buddhism, and later in American Transcendentalism and some of the more sober modern spiritual traditions. In all of these we see reflections of the Dude: principled but ordinary human beings who have managed to liberate themselves (to a degree[3]) from societal pressures, covetousness, worry about the future, and everything else that the engine of civilization would have us trust is important.

Our hero[4] the Dude is a thoroughly modern man who has made peace with his caveman mind, making sense of his exile from an erstwhile Eden to which he has been adapted. We would do well to follow in his sandal-steps, enrobing ourselves in a spiritual tradition which has helped perpetuate human sanity, down through the generations, across the sands of time.

So how does one become a Dudeist? Rather than make the same mistake as many of its ancestors, we are loath to try to identify any strict propositions or guidelines. To do so seems to always usher in an ossification of the original message. Instead we hope to lead by example – our own and those of philosophers, writers, comedians and deep thinkers that we identify as Dudeist. Our recently-published book, for example, The Tao of the Dude (Benjamin 2015) contains a compendium of Dudeist quotes and passages taken from a wide swath of world literature. As a sort of open-source religion, we rely on our followers to submit ideas, articles and events that might help us gather up our rosebuds (and other buds), promote the ethos, and learn to abide (Benjamin and Eutsey 2011). The best the organizational aspect of the religion can hope to do is provide a meeting place and sometimes break up the minor virtual online scuffle. See, even Dudeists are sometimes prone to lose their cultivated cool. However, they do tend to snap back rather rapidly – just as the Dude did moments after having the worst day of his life, deciding immediately that he “Can’t be worried about that shit. Life goes on, man!”

As far as what will “go on” for Dudeism, we’re having fun fashioning the roadmap. If we’ve allowed even a few people to take comfort in all this, well then, it’s been well worth the ramble.

References

Benjamin, Oliver. N.D. ‘Great Dudes in History’. Dudeism.com: Your Answer For Everything. At: http://dudeism.com/greatdudes. Accessed 8 September 2015

Benjamin, Oliver. 2015. The Tao of the Dude: Awesome Insights of Deep Dudes from Lao Tzu To Lebowski. Abide University Press.

Benjamin, Oliver and Dwayne Eutsey. 2011. The Abide Guide: Living Like Lebowski. Berkeley, CA: Ulysses Press

Church of the Latter-Day Dude. 2010. The Dude De Ching: A Dudeist Interpretation of the Tao Te Ching. Chiang Mai and Los Angeles, CA: Church of the Latter-Day Dude.

Coen, Joel and Ethan Coen. 1998. The Big Lebowski. Working Title Films/ Polygram Filmed Entertainment.

de Botton, Alain. 2013. Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion. London: Vintage.

Holy Bible: New Living Translation. 1996. At: http://www.nlt.to. Accessed 8 September 2015.

Jaspers, Karl. 1977. The Origin and Goal of History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Lao Tzu. 1963. Tao Te Ching. Translated by D. C. Lau. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Notes

[1] Wu wei is one of the central Taoist principles, and very hard to adequately translate. Something like “actionless action” or “action without striving,” it neatly describes the way that the Dude shambles his way through the world, going with the flow as much as possible, even under the direst of circumstances. Woo is the name of the character who sets the story in motion by urinating on the Dude’s rug, but it is also commonly used by rationalists to describe any pseudo-scientific New Agey mumbo jumbo. Taoism may have originated as a very rational understanding of human psychology but ended up becoming obsessed with pseudoscience.

[2] Not to be confused with our Dudeist translation of the Tao Te Ching, The Dude De Ching (Church of the Latter-Day Dude 2010).

[3] Dudeism maintains that there is no such thing as a saint. The best we can hope for is a “Sane.” (Note that there is the same relationship between “sane” and “saint” as there is between “whole” “healthy” and “holy”). That is to say that even the most spiritually adept among us lose our cool from time to time. The difference lies in the speed and facility in which we come back to our Dudeness. Though many have pointed out that the Dude loses his cool throughout the movie, he has a nearly supernatural ability to “abide” quickly after the inciting incident.

[4] The entire film challenges the notion of heroism, and doesn’t explicitly provide an alternative, so we might take a stab here – a hero for “our time and place” would provide a heuristic, or a model upon which we might reimagine ourselves and reorient our predispositions. Thus, a “heuro.” Note that our propensity towards wordplay is largely in the interest of deflating the manipulations of language, and should not be taken too seriously.

This article spoke to me on so many levels man. Thank you.

Lotta ins and outs, lotta what-have-yous. I’m going to enjoy diving into this site. Thanks!

This is a great article! I recommend that Haile Selassie be given serious consideration by the community – to be given the title of “Dude”.